Sibylle Rauch wasn’t just another face in the crowd of 1970s German glamour. She was the quiet force behind the scenes of Munich’s underground art and nightlife, a woman who moved between photography studios, jazz clubs, and artist lofts with the same ease as she did between languages. While her name doesn’t appear in every history book, those who lived through that era remember her as the link between avant-garde cinema, feminist expression, and the raw energy of post-war Munich.

How Sibylle Rauch Became a Symbol of the Munich Scene

By the early 1970s, Munich had shed its conservative postwar image. Young artists, filmmakers, and writers flooded the city, drawn by cheap rents and a growing tolerance for experimentation. Sibylle Rauch arrived from Bavaria’s countryside with little more than a suitcase and a portfolio of black-and-white self-portraits. She didn’t set out to be a star. She set out to be seen - on her own terms.

Her breakthrough came not from a magazine cover, but from a film still. In 1973, director Rainer Werner Fassbinder used her in a brief but unforgettable scene in Ali: Fear Eats the Soul. She played a neighbor who silently watches the interracial couple from her window. No lines. Just presence. That moment made her a cult figure among cinephiles. People started asking: Who is she? Why does she look like she knows something no one else does?

Her look - sharp cheekbones, dark eyes, a cropped haircut that defied feminine norms of the time - became a template for a new kind of German beauty. Not polished. Not commercial. Real. She wore thrift-store coats with designer sunglasses. She smoked roll-ups in cafés while reading Simone de Beauvoir. She didn’t pose for ads. She posed for friends.

The Munich Underground: Art, Sex, and Freedom

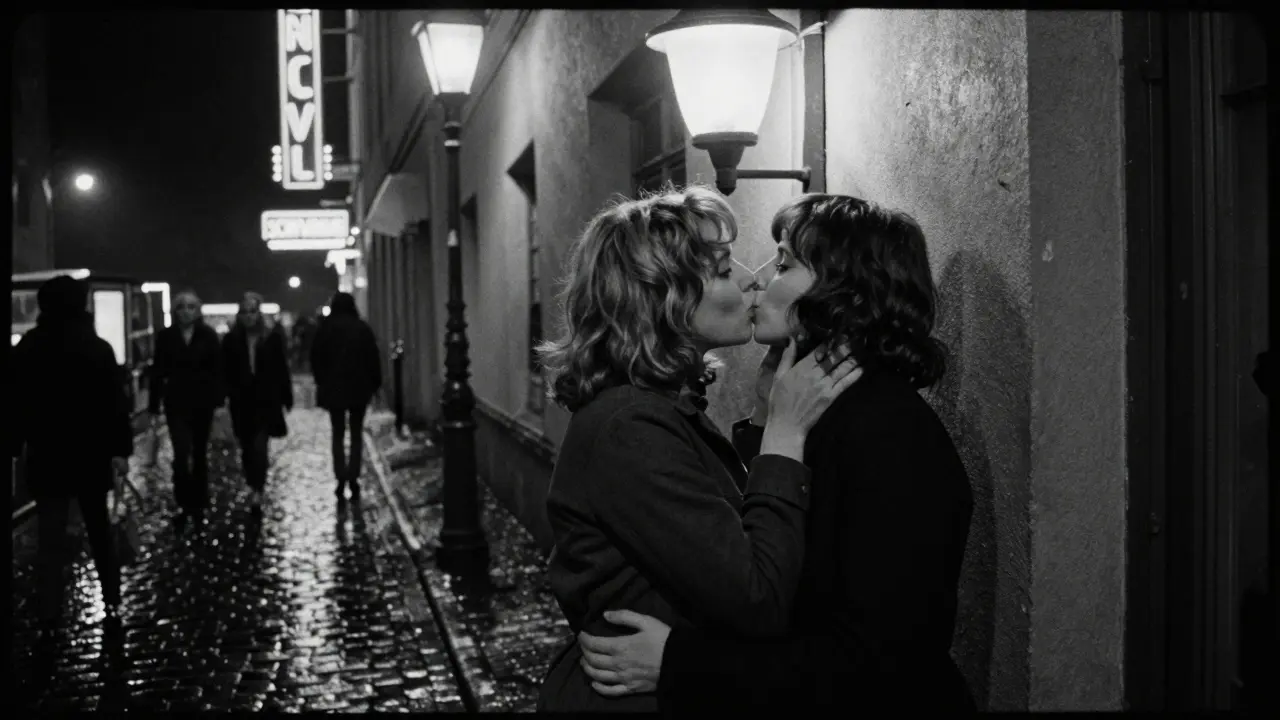

The Munich scene of the 1970s wasn’t about disco balls and bottle service. It was about rented lofts in Schwabing, poetry readings in basements, and late-night debates over cheap wine. Sibylle moved through this world like a ghost with a camera. She didn’t just attend parties - she documented them. Her photos, often taken on a Rolleiflex, captured moments others ignored: a woman sleeping on a couch after a film screening, a man crying in the corner of a bar, two women kissing under a flickering streetlamp.

She wasn’t part of any official movement. But her work became the unofficial archive of a generation. Her images showed women not as objects, but as subjects - tired, angry, joyful, confused. In a time when women’s bodies were either idealized in advertising or erased from public discourse, Rauch’s photos said: This is what it really looks like.

Her circle included figures like filmmaker Margarethe von Trotta, artist Rosemarie Trockel, and writer Christa Wolf. But she never sought fame. She didn’t want interviews. She turned down offers from Playboy and Elle. One editor told her, “You’re too real for us.” She smiled and said, “Good.”

Why the Munich Scene Needed Her

Munich in the 1970s was a city in transition. The old guard still held power in politics and business, but the streets belonged to the young. Women were demanding control over their bodies, their careers, their identities. Sibylle Rauch didn’t lead protests. She didn’t write manifestos. But she lived the revolution.

She shared apartments with male artists who didn’t pay rent. She worked as a set dresser for low-budget films to afford film stock. She taught herself darkroom techniques from library books. When she was offered a contract with a modeling agency that wanted her to gain weight and dye her hair blonde, she walked out. “I’m not here to be pretty,” she told them. “I’m here to be seen.”

Her influence spread quietly. Designers copied her layered outfits. Photographers studied her use of shadow. Feminist collectives printed her photos on flyers for rallies. She became a symbol not because she spoke out, but because she refused to perform.

Her Legacy: More Than a Face

By the 1980s, the Munich scene had changed. The energy faded. Many of her friends moved to Berlin. Others gave up art for steady jobs. Sibylle Rauch disappeared from public view. She moved to a small village near the Austrian border. She stopped taking photos. She started gardening. She rarely gave interviews.

But her work never vanished. In 2017, the Lenbachhaus Museum in Munich held a retrospective of her photographs - the first major exhibition of her life’s work. Over 12,000 people visited in three months. Critics called her “the silent witness of a liberated generation.”

Today, her photos are studied in art schools across Germany. Young women in Munich still wear cropped haircuts and thrift-store coats, not because it’s trendy, but because they’ve seen her face in a book and felt something click inside them. She didn’t want to be a role model. But she became one anyway.

What Made Her Different

Most models of the era were hired to sell something: perfume, jeans, a dream of perfection. Sibylle Rauch sold nothing. She offered truth. Her images didn’t ask you to admire her. They asked you to recognize yourself.

She had no agent. No publicist. No Instagram. She didn’t need them. Her power came from consistency - the quiet, daily act of showing up as herself, in a world that wanted her to be someone else.

That’s why, decades later, her name still comes up in conversations about Munich’s cultural soul. Not because she was beautiful. Not because she was famous. But because she refused to disappear.

Who was Sibylle Rauch?

Sibylle Rauch was a German model, photographer, and cultural figure active in Munich during the 1970s. Known for her raw, unfiltered presence, she became an icon of the city’s underground art scene through her work in independent films and her candid photography. Unlike mainstream models of the time, she rejected commercial gigs and instead focused on documenting real life - women, artists, and everyday moments - with honesty and depth.

Why is Sibylle Rauch associated with Munich?

Munich in the 1970s was a hub for experimental art, feminist thought, and countercultural expression. Sibylle Rauch lived at the center of this movement, moving between artist collectives, film sets, and underground clubs. Her photographs captured the spirit of the city’s rebellious youth, and her personal style and attitude became a touchstone for a generation rejecting traditional gender roles and consumer culture. She didn’t just live in Munich - she helped define its cultural identity during that era.

Did Sibylle Rauch ever become famous?

She never sought mainstream fame. While she appeared in Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1974 film Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, her role was small but memorable. She turned down major modeling contracts and avoided interviews. Her recognition grew slowly - first among artists and filmmakers, then among feminist scholars. A major exhibition at Munich’s Lenbachhaus Museum in 2017 brought her work to a wider public, cementing her legacy as a quiet revolutionary in German visual culture.

What kind of photography did Sibylle Rauch make?

Her photography was intimate, black-and-white, and deeply human. She used a Rolleiflex camera to capture unposed moments: women sleeping, friends laughing after a party, strangers in quiet conflict. Her images avoided glamour and instead focused on authenticity. She photographed her friends, lovers, and strangers with the same respect - never exploiting, always observing. Her style was influenced by street photography and feminist art movements, but her voice remained uniquely her own.

Is Sibylle Rauch still alive?

Yes. Sibylle Rauch lives privately in a small village near the Austrian border. She has not given interviews since the early 2000s and avoids public attention. She spends her time gardening, reading, and occasionally working on personal art projects. Her decision to live out of the spotlight has only deepened her mystique and influence among those who value authenticity over visibility.